Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

To determine whether the History of Discovery as we know it in the West is wrong and whether the Chinese, like the Vikings, should be credited with having visited America before Columbus.

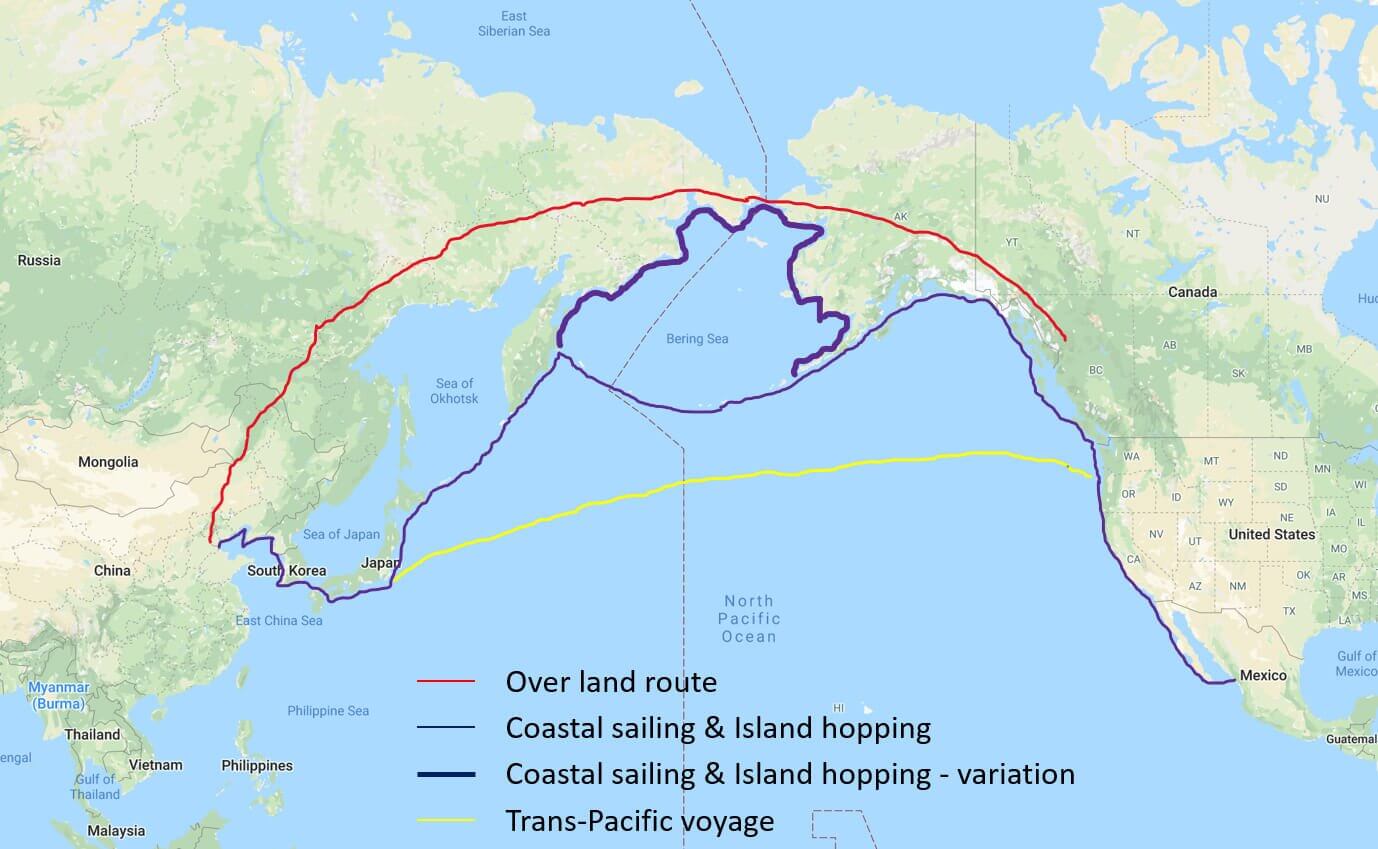

From the 16th to the 19th centuries many European academics (and clergy – the scientists of the day) agreed that the Chinese had somehow visited America long before Columbus, either via the Bering Strait, or by island hopping across the North-Pacific Rim, or directly across the Pacific Ocean aided by the Kuroshio Current.

However, Western positive sentiment towards China changed as a result of the 19th century Opium Wars (it is difficult to justify peddling drugs to high-culture people for commercial gain), and when Danish historian Carl Christian Rafn claimed in 1837 that, according to the Icelandic Sagas, the Vikings had visited America around year 1000, focus shifted onto the Vikings and the idea that the Chinese could have visited America before Columbus was increasingly ridiculed.

Yet, eminent sinologists, such as Joseph Needham, believed the Chinese had visited America before Columbus, but were unable to get traction on the subject.

“But what is the truth? Did the Chinese, like the Vikings, visit America before Columbus? That is what we aim to find out.”

Our project focuses on the time period, which spans from the beginning of the Qin Dynasty in 221 B.C. to the end of the Yuan Dynasty in 1368 A.D.. On purpose, the research stops before Zheng He’s seven voyages during the Ming dynasty, which Menzies and many other writers have already exhausted, and in which academics find no evidence of possible visits to America.

There is no doubt that Zheng He’s voyages mark the pinnacle of China’s maritime ability, but getting to that level of sophistication will have taken centuries. Very little research has focused on China’s seafaring ability before the Ming, and even less on Chinese maritime voyages in a North-Easterly direction because Zheng He’s voyages in a South-Westerly direction have always stolen the thunder. So maybe there are some historical “gold nuggets” out there waiting to be discovered, both in the history books and physically in the ground.

It was only in 1960, 123 years after the Danes had proposed that the Vikings had visited America before Columbus, that the archaeological proof validating this hypothesis was discovered in Newfoundland by Norwegian husband and wife team, explorer Helge Ingstad and archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad, who specifically went looking for it.

The fact that no Chinese archaeological evidence has been found in America to date does not necessarily mean it does not exist. Maybe it simply has not been found yet, because no one has looked for it in a systematic manner.

The first is about Xu Fu, alchemist and conman extraordinaire, who left China by sea in 210 B.C. with 3,000 boys and girls to establish a colony somewhere East of China. Xu Fu tricked the Qin Emperor into believing he was going into the Eastern Seas in order to bring back an Elixir of Immortality for the Emperor, which he would obtain from the Gods by bartering the 3,000 children.

This story is documented by China’s first historian Sima Qian 司马迁 (145-90B.C.), in China’s first official history book Records of the Grand Historian (史记).

Xu Fu of course never returned to China. Japan was already known to the Chinese at the time, so where else eastwards or north-eastwards of China could Xu Fu have settled safely, beyond the reach of the Emperor?

The second, and best known story, is about Fusang. In 1761 French orientalist Joseph de Guignes published an academic paper “Investigation of the Navigations of the Chinese to the Coast of America, and as to some Tribes situated at the Eastern extremity of Asia”, which caused quite a stir.

According to the official historical records of the Liang Dynasty, as recorded in the Book of Liang (梁书), then in 499A.D., a Buddhist monk by the name of Hui Shen showed up at the Liang Dynasty Court in China, having spent 50 years teaching Buddhism in Fusang with four other monks.

Since the Liang Court had never heard of Fusang, Hui Shen’s relatively detailed descriptions of the country and its habits were recorded. Fu Sang, according to Hui Shen, was very far East of Japan and he provided relatively detailed information about how to get to Fusang from Japan.

As a result, most European academics agreed that Fusang must have been a Chinese colony in America somewhere from Vancouver down to Mexico. Louis XV’s cartographer, Philippe Buache, even published a map in 1753, placing Fou-sang des Chinois north of California.

However, as sentiments towards China changed and the story that the Viking had visited America emerged, the interest in locating Fusang, or other Chinese pre-Columbus settlements in America, fizzled out.

“That is crazy to think about. To get from Beijing to Mexico City on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, the widest stretch of water you need to cross is only 36km, or to put it another way, only 3km wider than the English Channel!”But would the ancient Chinese have chosen to travel over land through Mongolia and Russia to get to the Bering Strait? It is doubtful. The Chinese have throughout history been afraid of the Barbarians from the North. That is why the first emperor of China, the Qin Shi Huang, ruler of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.), made sure the Great Wall was built so that the Barbarians from the North could be kept at bay. That worked well until the Yuan Dynasty (1271 – 1368 A.D.) when China was conquered by the Mongols from the North and came under foreign rule. The Chinese kicked out the Mongols in 1369 A.D. and founded the Ming Dynasty, but in 1644 another group of Barbarians from the North, the Manchus, invaded China and founded China’s last dynasty, the Qing Dynasty that lasted until 1911, when China became a republic. It is therefore likely that if the Chinese went North, they would have given the overland route a wide berth and preferred sailing via Korea and Japan where relations were friendlier.

There are many “proofs” in the Americas that the Chinese have been there pre-Columbus, but none of them withstand scientific scrutiny.

Should someone, some day, find a hard proof, then the question will still remains how it could have got there. If there is no plausible explanation, then the proof will likely be disgarded as having arrived post-Columbus, in order not to upset Western doctrine.

To date, a main academic assumption for getting from China to the Americas in pre-Columbian times is that the Chinese used the Kuroshio current off Japan to drift across the Pacific Ocean. Whereas this cannot be ruled out, it seems unlikely that the Chinese, or any other Asian nation for that matter, would have had the maritime technology and knowhow to willingly set out on a 8,000km non-stop Trans-Pacific voyage along a route, which would be impossible for an ancient vessel to back track. There is no mentioning in official Chinese history of Trans-Pacific or long off-shore voyages in pre-Columbian times (Zheng He followed the coast), so if such voyages took place, they are likely to have been by accident, not design, and one-way only.

It seems more plausible that the Chinese would have island hopped, just like the Vikings did, to get to the Americas. And, just like in the Islandic Sagas, official Chinese history does provide an island hopping account of how to get to “Fusang”, the Chinese equivalent of the Viking “Vinland”. But the Fusang story pre-dates the Vinland story by 501 years, so could the journey have been plausible that early?

Well, to get from Scandinavia to the Vinland the longest off-shore passage the Vikings had to make was 820km, wheras to get to America from China following the North Pacific Rim, the longest crossing the Chinese would have had to make is only 70km (less than 10% of what the Vikings did).

Moreover, the Vikings had to travel through mainly uninhabited regions bringing their own provisions, whereas the regions the Chinese would have had to travel through were populated, so they could have relied on local food, knowledge, and help to move forward. The Vikings were left to their own devices.

So, the navigational challenge the Chinese would have faced to get to America was significantly less than what the Vikings faced 501 years later and the route along the Pacific Rim can be followed in reverse to return to China, making it less scary to embark on the journey in the first place. Taking these factors into consideration, Chinese visits to America pre-Columbus start to look plausible.

The idea that the Chinese could have visited America before the Vikings and Columbus has generally been written off by Western academia, but just like Diffusionists have not had very good arguments for placing the Chinese in America pre-Columbus, then the Isolationists have also not had very good arguments for saying it never happened. The Gordian knot remains firmly tied, and it is the Isolationists who currently hold the rope ends.

If you ask the average Chinese where Fusang is, the answer is likely to be “Japan”, because this is what has been taught in school. But Fusang cannot be in Japan because the very same historical text that describes Fusang explicitly mentions Japan as a separate country.

The reason why China has placed Fusang in Japan may be because this is what the West did around the time of the Opium Wars, after first having placed Fusang in America. China was weak at the time and probably did not what to pick further quarrals with the West, which, within a very short period of time, rejected its darling Fusang story in favour of the Vinland story. The idea that the Scandinavian Vikings may have beaten Columbus to America, as opposed to the Chinese, was much more palatable in the West.

Academics did not really believe that the Vikings had been in America pre-Columbus, but in 1960 husband and wife team, explorer Helge and archologist Anna-Stine Ingstad, decided to use the Islandic Sagas as a road map to try and locate the Vinland. This led them to L’anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, where they found an old Viking settlement, which was excavated and the irrefutable proof that the Vikings had indeed been there in 1,000AD was uncovered. Suddenly, the Vinland story went from far fetched to fact.

There is further precedence that this methodology works. The Lost City of Troy was long written off by academics as mythical, until business man Heinrich Schliemann used Homer’s Iliad as a roadmap to locate the city in 1870.

“No one has used the Fusang story as a road map to try and find out where that may lead and what traces of the Chinese can be found along the way. This is what we aim to do. Whether we will hit jackpot like the Ingstads and Schliemann only time will tell.”

The route descriptions in the Fusang account from 499AD start in Japan, so it is lucky that there is another, earlier, account in Chinese history, Xu Fu’s Voyage East ( 徐福东渡 ), which brings the Chinese to Japan in 210BC.

Once we start to demonstrate progress and gain visibility this project will likely come under a lot of scrutiny from both academic and political circles in the West. It is therefore paramount that our academic research is first rate and beyond reproach. This takes time and requires on location visits to validate the Chinese “bread crumbs” trails we uncover along the North Pacific Rim in the direction of America. We also need to forge relationships with historians and museums along the way, who can help guide and validate our “bread crumb” search.

Because the Xu Fu story connects China with Japan and the Fusang story passes through two countries on the way to Fusang, then we have broken the project into four stages:

For each stage we first complete the academic research, including field visits to validate that the “bread crumbs” exist and that they are geniune. We then undertake an expedition from beginning to end of each stage to show that the journey would have been possible to make in ancient times using basic human powered maritime technology.

“What is the purpose of doing the human powered expeditions?”, you might ask. It is two-fold.

We show that the stage can be completed without modern technology relying exclusively on human power, which lends credence to the possibility that people in ancient time could have done the journey, too.

The second reason is to better disseminate our findings. Our academic research stand alone is unlikely to interest many people, apart from people who would prefer it goes away. By story-telling our academic findings through human powered expeditions in little known and often inhospitable places of the world, allows us to reach a larger audience and we also make ourselves more newsworthy for the media in general.

The expeditions are key to getting the message out there to a broader audience. People may reject our research on principle if communicated directly, but when story-told as part of an compelling adventure they may allow for it, which in turn may make them reconsider their own beliefs and the accuracy of the History of Discovery as we know it in the West.

So, if all goes to plan, this project will result in the re-writing of the History of Exploration as we know it in the West and start to shift focus from a White Man centric world view to a more nuanced view of the History of Discovery.

The ultimate success will be if in 10 years’ time the sign at the British Museum recognising that the Vikings visited America before Columbus will have been updated to include the Chinese (and/or maybe other Asians countries).

You can follow the ups and downs of this project via our Log Book.